George Baxter and his patented ‘Baxter Process’ prints

By Syd Exton (Chairman of the New Baxter Society) and Yvonne Smith

You may have come across one or two prints, whilst browsing online or rummaging through an antique shop, which carry the description ‘Baxter Print’. But what is a Baxter print? And who was Baxter? In this blog we will introduce you to George Baxter and his patented ‘Baxter Process’ prints.

George Baxter produced prints covering a wide range of subjects.

Left: So Nice, 1852, 15 cm x 10 cm. Right: The Ordinance of Baptism, 1843, 28 x 39 cm. The print shows a mass baptism in the sea in Jamaica on 2nd January 1842. Images © New Baxter Society.

George Baxter (1804-1867) was an important figure in the colour printing world. Even though there had been experiments in colour printing for many years, including William Savage’s ambitious colour prints in his 1822 work ‘Practical Hints on Decorative Printing’, by 1830 most prints were still either monochrome or hand coloured. But Baxter changed all that. He brought affordable, high quality decorative colour prints to the masses, and for 30 years produced a wide range of colour pictures.

George Baxter was born in Lewes where his father, John, had a printing and publishing business. His father wanted him to join the trade, but George was a talented artist and found himself drawn to illustrating the books rather than making them. He was apprenticed to a wood engraver and his first illustrations (black and white woodcuts) started to appear in his father’s books in 1824.

George Baxter, 1804-1867. From a photograph supplied by Mr Frederick Harrild, taken from the original in the possession of the family. Image from H G Clarke’s book, Baxter Colour Prints, 1919, Leamington Spa Courier Press.

In 1827 George married Mary Harrild, the daughter of Robert Harrild who was a manufacturer of printing machinery, and with backing from his father-in-law he set up his own printing business in London. About this time he started to experiment with colour printing and completed his first colour illustration in 1829. This is known as 'Butterflies' and shows three of the insects, one of which has alighted on a plant. The layout of the print suggests that it was to be used as a book illustration, but no such book has ever been seen. The print, produced from woodblocks only, is very rare.

It was four years before Baxter produced his next coloured prints which appeared in Robert Mudie's The Feathered Tribes of the British Isles (2 vols). The small title page vignettes in these two books were also from woodblocks only, and used traditional inks. Over the next six years Baxter provided illustrations for fourteen of Mudie's books and early on in this period he began to refine his process. He changed from printing from woodblocks only, to combining intaglio printing with woodblock printing, and started to use oil-based inks. These oil-based inks gave the prints a wonderful depth of colour.

By 1835 he had developed his method of colour printing sufficiently to apply for a patent. The Baxter Process, as it became known, involved the manufacture of an engraved steel foundation plate which contained all the fine detail of the print, the manufacture of a number of blocks, one for each colour, and the use of oil-based inks. In his early prints these colour blocks were made of wood, but he later also used metal blocks. Some of his prints used over twenty different colour blocks and the secret was to ensure that the alignment of each block was perfect; no mean feat when you consider the hand-operated presses which were used at that time.

A woodcut by George Baxter showing an Albion Press. Image from H G Clarke’s book, Baxter Colour Prints, 1919, Leamington Spa Courier Press. Baxter produced a number of woodcuts of printing presses for catalogues and advertisements for his father-in-law’s print machinery business, Harrild and Sons.

The ‘foundation’ or ‘key’ plate, usually made of steel, was created using line engraving, stipple, aquatint and occasionally mezzotint. This was an intaglio plate - the ink being held in the incised lines and grooves. When the metal plate had been inked and the surface wiped clean, ink remained in the engraved incisions and when put through a rolling press, the desired picture was reproduced on paper in monochrome. The colour blocks were engraved in relief - the surface being cut away to leave a raised printing area where the colour was required. Each colour was then printed in order using relief presses, such as the Albion Press made by Harrild and Sons, ensuring that each colour was carefully aligned in the correct position by using Baxter’s system of register dots/holes on the foundation impression, and locating pins on the tympan of the printing press.

Shown below is Baxter’s print The Day before Marriage, one of his ‘lovely ladies’ series, which he published in 1853. This was produced from a steel foundation plate, fourteen colour metal blocks, and some engraved wood blocks. In this case the wooden colour blocks were only used to add the detail of the hands and the face, some being inserted into holes within larger metal colour blocks.

The Day before Marriage, George Baxter,1853, 38 cm x 27.5 cm.

From left to right: the steel foundation plate (framed in the 1920s), an electrotype block (Deep Violetcolour) made from type metal and coated in copper, two small wooden blocks (Flesh colours), and the finished print. Images © New Baxter Society.

In all, Baxter produced over 370 different prints, giving up his business in the 1860s. The subject range is vast, from portraits to landscapes, from amusing pictures to scenes of tragedy.

Similarly, the size of the prints varied considerably: his largest picture, The Parting Look published in 1858 measures 65 cm by 47 cm, whilst his smallest book illustrations were only 7.5 cm x 6 cm. He also produced even smaller prints measuring only 4.5 cm by 2.5 cm which were used to adorn needle-boxes.

The number of copies produced of each print also varies tremendously. Baxter’s The Holy Family (after Raphael) was produced in prodigious numbers, perhaps as many as 700,000. At the other extreme, he produced a mere eight copies of his portraits of Mr & Mrs Chubb, for the locksmith’s family.

Baxter's choice of subject was varied, but he did produce a large number of prints on three themes: missionary enterprises, the Great Exhibition and the Royal Family.

From 1838 to 1847 in conjunction with the London Missionary Society, Baxter provided illustrations to many books with a missionary theme and, for the first time he published stand-alone prints. There are 36 prints in this group and they cover portraits of missionaries and illustrations of their life and work in the Pacific, China, Madagascar, Greece, Africa, India, and Jamaica.

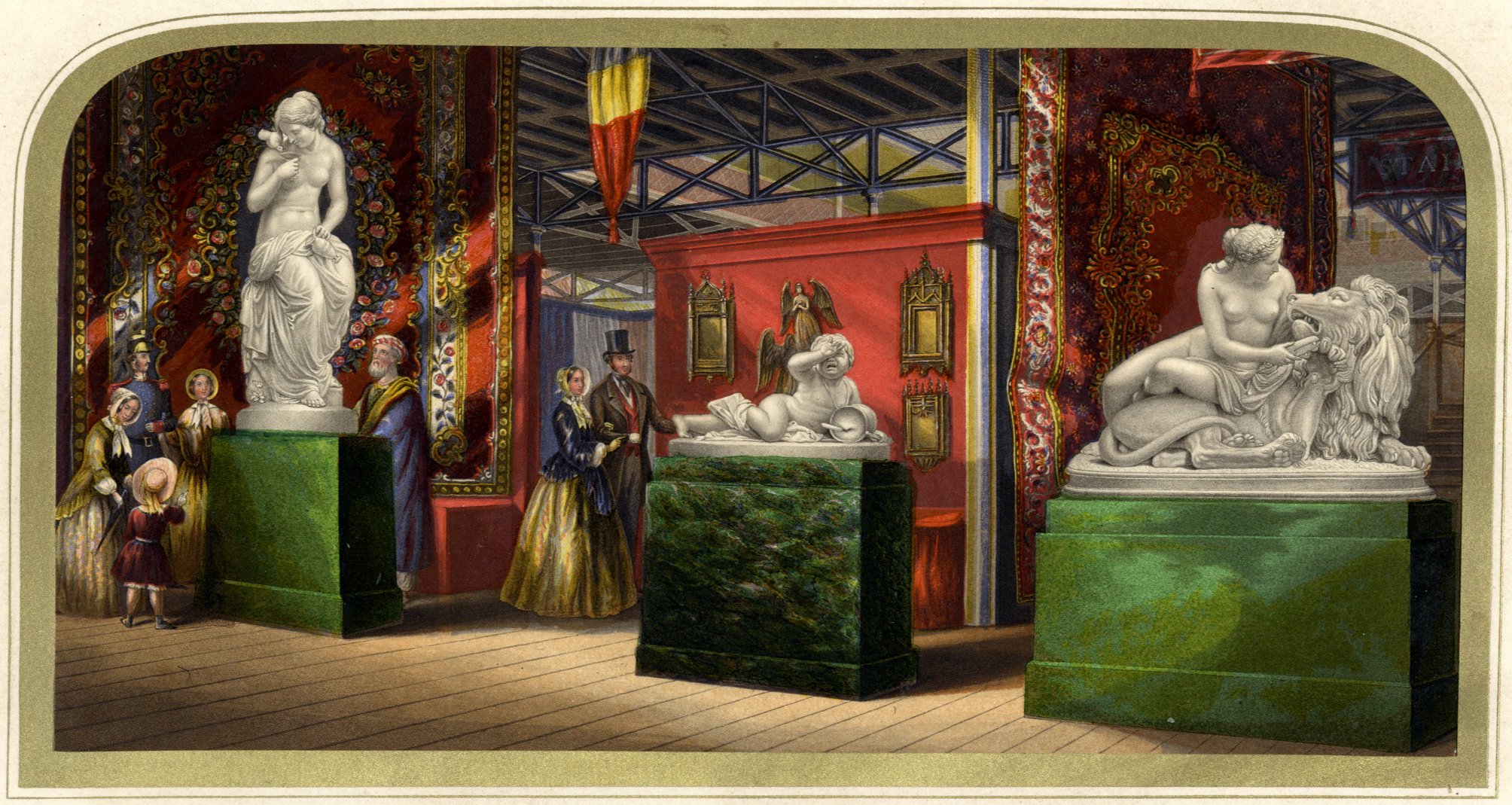

The second major theme is the Great Exhibition of 1851. Baxter produced fine prints of the exterior and interior of the Crystal Palace. His interior views concentrated on the statuary rather than the more mundane technological exhibits. He produced a short series known as 'The Gems of the Great Exhibition'. The first five of these each showed three statues; the prints are approximately 12 cm by 24 cm with rounded top comers. It is interesting to note the dress of the public moving amongst the statues and the prints serve as a little slice of history. Baxter produced 31 prints on this theme and another of the New York Crystal Palace.

Gems of the Great Exhibition No 2, George Baxter,1852, 12 cm x 24 cm. Image © New Baxter Society. The print represents a portion of the Belgian Department of the Great Exhibition of 1851.

Lastly, he produced 25 prints of royalty. Two of his best are The Coronation of Queen Victoria and The Opening of Parliament, both issued in 1841. In both cases, Baxter was given Royal authority to record the events and these large prints (55 cm by 44 cm) are full of detail. Indeed the former contains some 200 recognisable portraits. Such was his perfectionism that it took four years to finish them. By the time they were published, interest in the events had waned and they were not the commercial success he hoped for. These two prints can be found in various lengths, often the full length of the plate, but at other times cut dome-shape or half or three quarter length. It would appear that this was done by Baxter himself and not cut since, as his prospectuses state as follows: ‘Price, £5 5s. 0d.; large size, 21¾ x 17½, £3 3s. 0d.; small size, 17½ x 13¾.’

Her Most Gracious Majesty Queen Victoria receiving the Sacrament at her Coronation, George Baxter, 1841. The full size print measures 55 cm x 44 cm, and the small size 35 cm x 44 cm.

Left: the steel foundation / key plate (which was framed in the 1920s). Image by kind permission of Lettering, Printing and Graphic Design Collections, Department of Typography & Graphic Communication, University of Reading. Right: the smaller version of the print showing only the bottom half of the scene. Image © New Baxter Society.

Baxter’s original patent expired in 1849, at which time he was granted an extension of five years and was advised to sell licences to use his patented process. He granted licences to six other printers: Abraham Le Blond, Joseph Kronheim, William Dickes, Joseph Mansell, Bradshaw & Blacklock, and Myers & Co., and they all produced prints by the Baxter method, some more successfully than others. None, however, quite matched the quality and colour of Baxter’s own prints.

Le Blond was arguably the best of these ‘licensees’ and is renowned for his set of 32 oval prints which depict charming scenes of 19th century life, and which are of a very good quality. Le Blond also acquired many of Baxter's printing plates and blocks in 1868 after Baxter’s death and produced his own versions of many of Baxter's prints from these, often using less colour blocks.

Joseph Mansell largely produced small decorative prints which he used in his fancy stationary business, whilst William Dickes mainly produced his prints as book illustrations or for reward cards for the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SPCK).

It was Kronheim, however, who was the most prolific printer using the Baxter Process. Much of his effort went into illustrating books, including many Religious Tract Society books, but he also produced many fine prints of a larger size. A huge collection of uncut sheets of Kronheim prints, in mint condition, was discovered in 1981 and vast quantities were released on to the market. For this reason, Kronheim prints are the most commonly found of all the Baxter Process prints, and usually the most pristine.

By the time of Baxter’s death in 1867, powered lithographic machines had been introduced by many chromolithographers. Competition was fierce and those printers still using the Baxter Process had to adapt to compete. Some started to use fewer colour blocks, whilst some turned to chromolithography. Times were changing and it soon became clear that the Baxter Process, although more than equal in quality, could no longer compete on price and had run its course.

If you would like to explore the incredible prints of George Baxter further, you can view many examples of his work online as numerous collections such as those held by the British Museum and the E J Pratt Library sat the University of Toronto are now being digitised. Or you could visit one of the many public collections such as those held by the V&A, Reading Museum, Maidstone Museum, and the Hatton Gallery in Newcastle upon Tyne (please check access arrangements before you visit). Many of these impressive collections were assembled in the 1920s, the heyday of Baxter Process prints when the rarest prints by Baxter sold at auction for more than a Canaletto! But now, thanks to generous donations in recent years by members of the New Baxter Society, what is probably the largest collection of Baxter and licensee prints in the world can be found in the Special Collections Museum at Manchester Metropolitan University, whilst an extensive collection of the printing plates and blocks of George Baxter and his licensees can be seen at the Department of Typography & Graphic Communication at the University of Reading, along with numerous presses which they have used on occasion to print from some of Baxter’s plates.

The New Baxter Society is a not-for-profit organisation concerned with the collection, preservation and study of the colour prints of George Baxter, his Licensees and other Nineteenth-Century Colour Printers. The New Baxter Society provides information for the general public about George Baxter and his Licensees, and assists public organisations with the cataloguing of their collections. Members receive extended information and regular newsletters.